- Home

- Richard Brewer

Culprits Page 13

Culprits Read online

Page 13

“You need ropes and lights and other equipment to manage that hole,” Big Jim said. “No one’s ever been all the way down, not since one of the passages caved in, makin’ it more narrow and dangerous. We had a kid trapped in there a few years ago, the Muncy boy, about twelve. His brother was with him when he fell in or no one would’ve ever known he was down that thing. He got stuck on a ledge, one leg hangin’ on by a hair, really. Couldn’t move up or down. Took us about eight hours to get him out. It ruined him. He ain’t been right in the head since then.”

“Jesus,” Tony said.

“I put up signs and roped off the hole and even tried to get the town council to allocate money for blastin’ the damn thing shut. But kids pay no mind to signs and the town council wouldn’t okay anythin’ without the city attorney’s approval, and that ain’t happenin’, not from that son of a bitch.”

Tony didn’t ask why. He didn’t really care. He wondered how far down the hole Vivian had crawled to hide the money. She could go deep if she had to. Deeper than either he or Big Jim could manage.

They drove for several more minutes until Big Jim slowed down, almost stopping.

“She’s still here.” Big Jim pointed to something in the darkness. “Thought we’d missed her. She should be streakin’ for Dallas.”

He parked about a hundred yards from the ridge. He switched off the interior light and quietly opened his car door. He walked slowly, hunched over.

Tony jumped out of the SUV. He carried a flashlight and hooked Big Jim’s extra gun in his belt. His fingers twitched in anticipation.

The long almost flat ridge stretched against the early morning sky. Rays of moonlight bounced off the black silhouette of his truck. A slight breeze caressed the men, who didn’t notice.

They inched up to the layer of horizontal rock that marked the opening in the Texas earth. They stared into the darkness and for a few minutes they saw nothing but the darkness.

“Hear that?” Big Jim whispered.

Tony listened. He heard the breeze against his ears. Then, something else. A groan, or a sigh. A soft sound tinged with pain. Tony stared harder into the cave.

She lay on her side, not moving.

Big Jim stood up. He slowly walked into the opening and almost immediately he had to stoop so he would fit. Tony followed.

Vivian lifted her head. “Took you clowns long enough. Feels like I’ve been laying here for hours.”

Tony switched on the flashlight. Vivian stretched along the floor of the opening, crammed against the wall of the cave where it narrowed into the shaft. Her right ankle twisted at a weird angle and Tony could see that it had already begun to swell.

“You fell?” he said.

“Of course she fell,” Big Jim said. “You moron. That ankle. Looks broken. Looks ugly.”

“Yeah, I fell.” Resignation filled her voice. She groaned. “I climbed down that goddamn hole until I got to the ledge where I had the bag. I grabbed it and was shimmying out, up on my knees, when something slithered across my arms. I don’t know, I think it was a snake. Something.” She stopped talking and let go of the tension in her neck. “I didn’t handle it like I should’ve,” she continued. “I jerked away, lost my balance. Did everything I could to not fall backward into that shaft, so I fell forward. Landed funny and my ankle collapsed. I hit my head and must’ve passed out. Don’t know how long. I was coming around when I heard you outside. Of course it had to be you two.”

“A snake?” Tony said. He aimed his flashlight away from Vivian. “That thing still here?”

Tony and Big Jim saw the canvas bag of money against the wall at Vivian’s back. They both rushed to the bag. Tony lunged for the stash. He dropped the flashlight, pulled the .45 from his belt, aimed it at Big Jim, and backed against the wall. One hand held the bag, the other his gun.

Vivian snatched the light and pointed it at Big Jim.

Big Jim aimed his gun at Tony.

“Give me that money,” Big Jim barked.

“Go to hell,” Tony answered.

“Easy, boys,” Vivian said through gritted teeth. “You can shoot each other, just let me out of the way.”

“Shut up, bitch,” Big Jim shouted. “Give me that money, Garza, or you ain’t leavin’ this hole.”

“Then ain’t none of us leaving,” Tony said.

“I got plans for that cash,” Big Jim answered.

“I’m sure you do. And they don’t include giving it back to Harrington. Chief of police, my ass.”

“You’re not one to judge me, boy.”

“Aw…” Tony sighed. He pulled the trigger of the .45 and Big Jim slammed to the ground. Big Jim’s gun flew into the blackness of the cave. He rolled in the dirt, clutching his right knee.

“You son of a bitch!” Big Jim screamed.

Tony had to finish off Big Jim, then Vivian. He stepped over Vivian to get closer to Big Jim.

Vivian turned the light into Tony’s face, blinding him. She hit his upraised leg with the flashlight and he fell to the side, arms flailing, hands clutching at the air. His eyes flared open. He tried to keep upright but his feet slid out from under him. The gun dropped into the hole. He followed it, hugging the bag.

Tony screamed as he bounced against the walls of the shaft. The screams stopped with a dull thud.

“Oh my God,” Big Jim said. “You lost the money. And you killed him Oh my God.”

Vivian struggled to her elbows.

“Well, now I got no choice,” she said. “You two screwed the pig royally. Have to get out on my own.” She looked around the cave. “I’m leaving and you’re not stopping me.”

“I’m shot, bleedin’, in case you hadn’t noticed.”

“You’ll live. As long as you get that bullet hole looked at soon.” She caught her breath. “Guess you could bleed out.”

Big Jim shuddered. “You have to help me. I can’t stand up, can’t walk. You can’t neither. Together, we can get back to town. The doc’ll take care of both of us. Then you can disappear, leave. You’re not my problem. I don’t care about you.”

“You mean now that the money’s gone, eh? And Tony?”

“No one will miss him. He’s history. Happens all the time around here. People come and go. No one will look for him and for sure no one will look at the bottom of that hell hole.”

She painfully maneuvered to her knees, then forced herself to stand on her good leg. Sweat covered her face. She picked up a piece of dried cholla wood and used it to steady herself. Her ragged breathing echoed against the cave walls.

“That’s a great offer. But I think I’ll pass.” She examined her ankle under the beam of the flashlight. “Christ, this could take a while.”

“I can help. We can help each other. I’m tellin’ ya.”

She pointed the flashlight in the direction of the cave opening. “Maybe someone will notice your car and come around. Yeah, that’s probably what will happen.” Big Jim frantically shook his head. “They’re gonna ask where you are sooner or later.”

“You can’t leave me. I’ll bleed to death.” His blood-covered fingers hugged his knee. Blood soaked his jeans.

A few hundred dollar bills lay on the ground. She stuffed them in her pockets. Five hundred.

A ray of morning light streaked into the cave.

She leaned against the wall and accepted that the walk to Tony’s truck would be the longest walk she had ever taken. She breathed deeply, three times. Her training taught her to envision what she had to do, what the obstacles were and how she would overcome. The first goal was to get out of the cave, then make it to the truck. Retrieve Tony’s gun from the glovebox, where she’d left it. Then she would detail the next step. Driving the truck. Staying alert. Avoiding the roadblocks and helicopters. Dealing with the pain. Finding someone to help her. She thought she had a chance. Not much. But a chance.

She limped to the light.

Chapter 7 - Eel Estevez

/> By Joe Clifford

Eel Estevez had always hated the heat, since he was a little kid. The way the dry got caught in your throat, the clog of dead things choking passageways, cutting off the esophagus, making it hard to breathe. In the desert, water was scarce, and in the shantytowns of his youth, even more so. He remembered the price his mother paid before she died. Scrubbing rich men’s toilets in their air-conditioned mansions, sent back to the swarthy El Paso slums covered in shit, left to bake in a little clay hut. How his father died like a dog in the scorched fields. The heat was like the cancer that killed him. It consumed you, whole. Cooked you alive, from the inside out. What did it say, then, about a man who’d chosen to live his entire life sandwiched below the thirtieth parallel? Even when he got out of El Paso, Eel hadn’t escaped the heat. A brief, fruitless stretch in the Army landed him at Fort Huachuca on the Arizona-Mexico border.

Eel stretched, a blast of morning light winning the war against bent motel blinds. He glanced back at the woman. A big gal. Not fat. Full figured. Like that plus-size model they recently put in the swimsuit issue, one of those sports magazines trying to prove that we’re progressing as a society; it’s okay to love all shapes and sizes. Ashley something. The model. Not the girl. He couldn’t remember her fucking name. His head throbbed like it had been back-kicked by an extra stubborn mule with restless leg syndrome. Political correctness had even found a way to weasel its ugly head into soft-core porn.

He didn’t care about the girl in his bed, and he didn’t bother fishing the name of the sports magazine from the gray matter either. America didn’t give a fuck about fútbol, or soccer as they called it here, so Eel didn’t give a fuck about American sports. His love of fútbol was the one thread tying him to his homeland. Which wasn’t much of a homeland at all. He’d never lived there. The color of his skin meant he’d never be fully embraced here either. He was a man without a country.

This was why Eel didn’t go back to Mexico with Carter all those years ago. At least that was the reason he gave. There were other, more significant prejudices, harder to admit, confess aloud, not the least of which was that Eel felt no connection to his heritage. Never had. He was more gringo than most of the gringos he knew. He may not have felt particular allegiance to the States, but he was born in America. What difference did it make what was in his blood? It all spilled the same color.

Carter had had a hard time understanding how Eel, a Mexican, pure bred and blue, could feel no sense of community, no allegiance to what flowed in his veins. Geography, Carter had said, is an address, before pointing at his heart. “But this is who you are.”

The only time Eel and he ever got in a fight was that night Carter left, when he called out Eel for his lack of loyalty.

“It’s where we belong,” he’d said. “Mexico is our home.”

By then, Eel’s parents were both dead, Carter the closest thing to family he had left. But he didn’t feel like learning the ins and outs of a foreign culture, mapping different streets, new customs.

“Our home?” Eel said. “We have lived in Texas our whole lives.”

“And what good has that gotten either of us?”

At that point, Eel still wasn’t Eel, he was Estaban Estevez. He wouldn’t become Eel until later. But Carter was already Carter, having made the switch from Diego Rodriquez long ago. That night, however, what they called one another hardly mattered; they were just two boys who’d run the gamut from boosting to two-bit robbery, at a crossroads, deciding to take different career paths. Carter was going home, enlisting full-time, signing up for his fate. He had a connection to the drug trade, where the real money was to be made, and wanted Eel to join him. Eel still thought there was good in him.

“I know who I am,” Carter said. “What I am.”

“You?” Eel had mocked. “You? The one pushing a return to Mexico? You—Diego—who made up your own nickname from an American movie.”

They’d grown up on those gangster flicks, Scarface, Carlito’s Way, renegade cowboys, Butch, Sundance, the travels and trials of one-eyed fat men. It was a low blow and a deep cut.

They pushed. They shoved. In the end, no one threw a punch. Soon it was over. This was meant to be a celebration. So the boys forced themselves to laugh, have fun, trading swigs from the bottle, knocking back round after round in a border bar with the hole in the floor that smelled like hot piss and grease splatter. Sealing the sendoff by slitting hands with an all-purpose pocketknife on the curb of an all-night pharmacy. This wasn’t goodbye. They’d see each other again. They both knew then some bonds were forever, thicker than blood.

. . .

Eel had a lot of rules he lived by, or at least he used to, the first of which had been: no matter how tough you think you were, there was always someone tougher. Maybe it was because it had taken Eel Estevez so long to find that man that he’d forgotten. He’d gotten cocky, arrogant, reckless. As soon as you thought you were on top of the world, you could count on the world coming up behind you to kick you in the ass.

After the shitstorm at the ranch, while Benny and the others were racing off, thinking they’d won some sort of skeet-shooting jackpot, Eel knew better. Too many guns..Too much trouble for a run-of-the-mill smash and grab. Eel spirited toward open roads, all of which headed south, leaving the wreckage in his rearview, with nothing to do but think. Eel wasn’t stupid. He knew damn well what he was getting himself into. But that much money? It had been easy to convince himself of untraceable pickings. Plenty of blame to go around. There were countless funnels and monies off the book, the whole state of Texas rife with them, sitting right next to the border, quick access to spin a fresh load, tumble dry cash, spit it out clean. Half a million was pocket change to these men. What did Eel care if a few politicos were greasing palms to pass a zoning ordinance? The price of doing business in a free market economy. But no, that response had been too swift, too efficient and clusterfucked at the same time. Left a bad, bitter taste. It reeked of a set up.

Took a few days and a lot of miles. Phone calls. Inquiries. Calling in favors. The big one to Carter. It wasn’t like the friends ever fell out of touch.

Carter had done well for himself south of the border. Better than well, in fact. Carter’s reputation rivaled that of Clovis Harrington, the man Eel and his cohorts had just robbed, the man whom Eel should’ve known better than to go after. But not because of what Harrington was. It was the men Harrington really worked for. The monsters behind the curtain.

Carter confirmed what Eel already knew. That money they stole? Cartel money. He left Eel to wonder. Juárez? Zeta? Didn’t matter. He wasn’t walking away from this. He would be hunted down, propped on a post in the Sonora, innards picked clean by vultures and coyotes. His best chance was to broker a deal. Make a trade. Eel was no snitch. But self-preservation trumped all. Carter could be the go-between.

He watched the motel parking lot. No cars other than his, which he’d traded out twice on the road. Untraceable. No motorcycles. No trucks. Nothing but the heat. Vapors rose from the tarmac, gasoline sheens dancing, shimmering in waves. Eel hated waiting almost as much as he hated the heat. But Carter had said to wait. So Eel had no choice but to sit tight. Of course, this extra time meant too much time to think. And not just about the fuckjob on the ranch, his partners who, if they weren’t dead yet, were being hunted like game, exterminated one by one. Whether they knew it or not. No, Eel Estevez remembered being a boy, how his life might’ve turned out differently had he gone with Carter back to Mexico. He sure as shit wouldn’t be in this mess. Eel hated dwelling on the past, regrets, alternate futures. It was ridiculous, pointless. It was what it was, would be what it would be.

You know how I knew I was a thief? I knew I was a thief when I stole….

Eel laughed when he thought about those two skinny Mexican peckerwoods living in El Paso. Two boys in love with being outlaws before they even knew what such commitment entailed, glossed-over lessons learned from actors pretending t

o be the renegades they hoped to be. Some boys wanted to be heroes. Not Eel and Carter. They longed to be the bad guys, rooted for the villains. Eel just fought it longer, tried to take the righteous path, enlisted, did just enough to get honorably discharged. But all roads lead you back to who you really are, eventually. Carter had always been the smarter of the two.

Eel picked up what was left of a bottle, drained the dregs, lit a cigarette, and peered out of the blinds into the sweltering parking lot. Those vapors kept rising from the tarmac, smoking snakes, diablos distorting fields of nothing across the two-lane road. Dry tumbleweeds and tinder brush, snapped coils from the staked posts, whiplashed and now lying flaccid in the dusty culverts. He checked the bedside table. The motel clock either hadn’t been plugged in, or had been ripped from the socket in the throes of inebriated, high-octane sex. What was this girl’s name? His head swirled. He shouldn’t have drunk so much. But goddamn he hadn’t wanted to be in his head last night. His dead grandfather’s voice crept in once more. The last time Eel snuck south of the border, when the old man was dying. To see him one last time.

“That is why crime pays so well, mijo,” the old man said. “Because it’s illegal.”

His father, on the other hand, Auturo, did not judge his only son for his chosen vocation. A farmer who’d toiled for nothing but fast-acting cancers and an early grave, the senior Estevez all but gave his blessing for the path Eel chose to take. In the movies, American movies, they always showed the honest, hard-working father imparting lessons on their wannabe criminal child, trying to talk sense into them to do the right thing. Drive a bus. Work in a factory. An honest day’s wages for an honest day’s work meant more than all the riches in the world. Bullshit. Lies. Chupapingas. Money doesn’t buy happiness was just what the rich told you so you didn’t go after their gold.

Of all the jobs, this one…this one should’ve been easy. Until that fucking pilot and his buddy had to get greedy. His own men. What ever happened to honor among thieves? Another bullshit lie Hollywood sold.

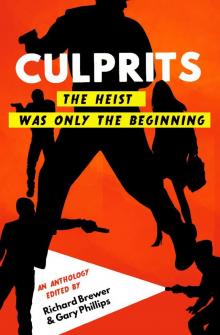

Culprits

Culprits